As 2022 drew to a close, every other day seemed to bring news of more layoffs. Soaring inflation had media executives speculating about a possible recession, and companies raced to lay off employees amid the uncertainty. CNN, Gannett, BuzzFeed, The Washington Post, Vice Media, Outside, Morning Brew, Protocol — the list kept growing.

The journalists at The Buffalo News, however, were feeling cautiously protected. They hadn’t completely escaped cutbacks — they had recently downsized from the building they’d occupied since 1973, and they’d lost two positions on their photo desk. But the mass layoffs that plagued other media companies didn’t seem imminent.

In fact, many felt a sense of optimism. They had heard that the News was doing fairly well and making money. The paper also had a new executive editor, Sheila Rayam, who arrived in August and was the first Black person to hold the job.

In late December, some journalists approached Buffalo Newspaper Guild president Jon Harris about the possibility of bonuses. The paper had just finished an exhausting year covering tragedy after tragedy. First, there was the mass shooting on May 14, in which a white supremacist killed 10 Black people at a supermarket. A few months later, in August, writer Salman Rushdie was stabbed in Chautauqua, just 80 miles away. November saw a record-setting snowstorm, and disaster struck again in December when a blizzard killed 47.

After a year like that, the journalists asked Harris, would it be possible that the paper’s owner, Lee Enterprises, might reward employees with bonuses?

The reporters got their answer in mid-January when Lee announced that it wanted to slash the newsroom budget by $1 million. In the days that followed, the News lost four veteran journalists due to cuts and paused hiring, eliminating several open positions. Lee then announced plans to cut the paper’s award-winning design desk, wiping out five more jobs. Next came a call for employee furloughs to offset a downturn in advertising revenue. And on Feb. 20, just 39 days after the cuts began, Lee said it would close the News’ production facilities and outsource printing to Advance Publications’ Plain Dealer in Cleveland, three hours away, affecting another 160 jobs.

Amid all of the cuts, employees grappled with shorted paychecks and large out-of-pocket expenses for routine health care, issues that arose when the company changed payroll administration and insurance providers.

Seeking answers from Lee has proven difficult as the company’s communication has been virtually nonexistent, enterprise reporter Mark Sommer said. He said a member of upper management told him that if it weren’t for the union, they wouldn’t know what was going on.

In late January, Lee vice president of local news Jason Adrians and East region local news director Paige Mudd visited The Buffalo News. The union asked them to hold a meeting with the newsroom to explain the company’s strategy, but Adrians and Mudd declined, saying their schedule didn’t allow for it. Instead, they would try to schedule one in 90 to 120 days.

Buffalo News publisher Tom Wiley and Rayam referred inquiries to Lee Enterprises spokesperson Tracy Rouch, who declined to comment for this story.

The recent events have demoralized staff, who take pride in working at the largest paper in upstate New York. The Buffalo News prints seven days a week and ranks among the top 25 biggest newspapers in the country by circulation. In Buffalo, the second-largest city in New York, the News is the main news outlet — the one that “sets the news agenda in this town every day,” as former News political reporter Bob McCarthy put it.

For decades, the News dodged the worst of the spiraling cutbacks that have decimated local newspapers. It enjoyed the protection that came from being billionaire Warren Buffett’s only daily at the time. Even as Buffett acquired more newspapers, he kept the News separate from the rest of his portfolio, giving the paper significant autonomy in its operations.

But The Buffalo News under its new ownership is now finding it isn’t protected anymore. And that realization has staff fearing for what’s ahead.

“We were feeling pretty, I think, encouraged overall about the future,” said Sommer. “And then to have all of this happen suddenly, it’s like a dose of reality or a blast of cold water on us, where suddenly the rosier outlook we were hoping to believe in came to a crashing halt.”

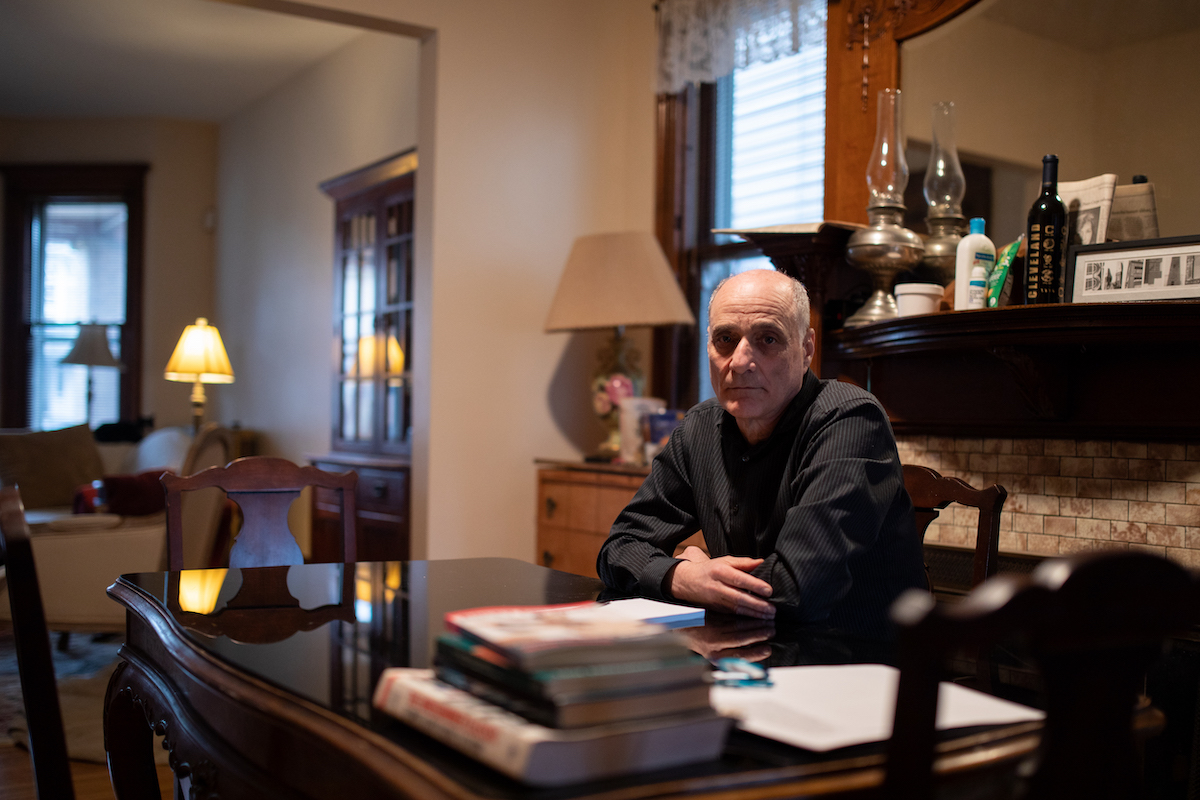

Former political reporter Bob McCarthy entered 2023 with no intention of leaving the job he’d held for the last 31 years. By Feb. 6, he and three other veteran journalists were gone due to Lee’s cuts. (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

Cutting the rank and file

For almost 40 years, Bob McCarthy made sure to stop by the Buffalo Irish Center for St. Patrick’s Day. That’s where all the major political players from the area gather to drink and talk and celebrate the holiday, so he works the room, gathering tips and story ideas.

This year, McCarthy found himself on the sidelines. Instead of identifying stories and issues he could bring to the attention of readers, he fielded questions about retirement. It is a phase of life that McCarthy, the News’ former political reporter, wasn’t ready for.

At 68, McCarthy knew retirement was likely a few years away. He had been at the paper since 1982 and had spent the last 31 years covering politics. But he loved the camaraderie of the newsroom, and he loved his job, which put him at the center of everything.

Lee upended his plans. In mid-January, the company informed the union that it wanted to cut $1 million from the newsroom budget. As part of those cuts, the company sought three layoffs by the end of the month. The union said its contract allowed it to seek volunteers first.

McCarthy had a week to make his decision. He knew he wasn’t in danger of being laid off. A junior staffer with the least amount of service would be let go instead. In the end, McCarthy decided to move up his retirement plan, in large part because of Lee’s “pretty generous” buyout offer, which involved roughly a year’s worth of salary.

“I said, ‘This is going to happen at some point, and if I don’t do it now, I’ll probably kick myself for not doing it later,’ ’’ McCarthy said. “But it was not something that I was prepared to do, and so I did it with great sadness.”

For nearly 50 years, The Buffalo News occupied a five-story building in downtown Buffalo. “It was a very architecturally significant building that I think exuded the power and influence … that the News always exerted,” former political reporter Bob McCarthy said. (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

Investigative reporter Matt Spina and home and style editor Susan Martin, both in their 60s and considering retirement, also volunteered to leave. The three had a combined 98 years of experience at the News. Lee also laid off news editor Paul Ehret, who had been at the paper for more than 40 years.

As union members gathered to say goodbye to McCarthy, Spina and Martin, the guild received official notice from Lee that it was cutting the News’ editorial design desk, affecting five more journalists. The desk, which had once won 55 Society for News Design awards in a single year, would be gone by June 14, their work outsourced to one of Lee’s design hubs out of state.

Two weeks later, Lee was back with more. This time, the company was implementing furloughs for its employees due to declines in advertising revenue. Employees making at least $20 an hour would take one furlough week before May and another before the end of September. The union pushed back, citing its contract, and agreed to offer members the option of taking a furlough but would not require them to.

Several days later, Lee announced it would close the News’ production facilities and outsource printing to Cleveland, three hours away, affecting another 160 jobs.

Meanwhile, Lee’s other papers were also undergoing cuts. The company’s 12 unionized newsrooms, which include the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Omaha World-Herald, tracked more than 50 job cuts at their papers since the beginning of the year. The World-Herald lost 25% of its newsroom staff and more than a dozen advertising employees. In Virginia, Lee laid off all but one of its opinion editors, effectively eliminating local editorials for all its papers in the state aside from the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

The union at the Post-Dispatch, Lee’s largest newspaper, had roughly 450 members in 2005, when Lee bought the paper from the Pulitzer family for $1.46 billion. Now, the union has 77 members.

“We’d already taken some beatings over the years. Buffalo, because it was owned by a different company, had not,” said United Media Guild president Jeff Gordon, who is also a sports columnist for the Post-Dispatch. “So we know that Omaha got pounded. Buffalo got pounded. We had already been pounded over the years. We’ve just taken the beatings year after year after year.”

Details about cuts at the company’s other 65 papers have been sparse. Lee did not answer a question about the number of companywide layoffs. Journalists at several papers have reported two-week furloughs. Last year, Axios reported that Lee planned to cut more than 400 jobs in 2022. In the company’s annual filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, it revealed that it had gone from a headcount of 5,130 in 2021 to 4,365 in 2022.

Lee reported a $97,000 profit in the 2022 fiscal year, a dramatic drop from $24.8 million in 2021. One major reason was a large increase in costs incurred while the company fended off investment firm Alden Global Capital’s hostile attempt to take over the company.

Still, the Buffalo Newspaper Guild noted that compensation for Lee executives, including president and CEO Kevin Mowbray and vice president and CFO Timothy Millage, increased last year.

“They’re cutting from the rank and file, but they’re making more money,” Harris said.

After graduating in 2013, Jon Harris worked first at the Gannett-owned Binghamton Press & Sun Bulletin before going to the Tribune-owned Morning Call. After Alden bought Tribune, he landed at the News, just in time for Alden’s hostile takeover attempt of Lee. It’s been a decade of “running from bad local news owners.” “No matter where you go in local journalism, as long as it’s owned by a chain, there’s major, major challenges,” he said. “I’m kind of almost tired of running from it.” (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

Centralization

The 150-year-old Buffalo News is used to operating with relative autonomy. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway acquired the paper in 1977, and for decades, it was the only daily newspaper the company owned.

“That was the first paper he (Buffett) ever bought. He really had an interest in it,” said Lee Coppola, who worked at the News from 1967 to 1983. “I met with him a couple of times on stories that he wanted done, and I thought, ‘This man cares — cares about journalism.’”

Even as Berkshire Hathaway started buying up small and mid-sized papers in 2012, creating the BH Media Group, the News remained separate. In a letter to the editors and publishers of the newly acquired papers, Buffett wrote about his love of newspapers, calling himself an “addict.” He acknowledged that the industry had changed since 1977, but said he still saw a future in newspapers that intensively cover their communities.

“Our newspaper purchases are of smaller size, measured by dollar cost, than the businesses we normally consider buying,” Buffett wrote. “But the papers are every bit as important to me — and, for that matter, to society —- as other businesses we have purchased for many billions of dollars.”

Seven years later, Buffett predicted in a 2019 interview with Yahoo Finance that most newspapers would eventually disappear. The news business, he said, was “toast.” The next year, he sold The Buffalo News and BH Media Group’s 31 daily newspapers to Lee Enterprises for $140 million.

The News, which had enjoyed relative independence in its operations until then, was now just one of Lee Enterprises’ 77 newspapers.

The company quickly made it clear that it wanted to centralize operations across its papers, which meant outsourcing jobs at the News. When Lee took over in January 2020, the guild represented 158 employees, including 82 who worked in the newsroom. Now, the guild represents 90 employees, 57 of whom are in the newsroom.

The newspaper industry has suffered significant declines over the past few decades — trends the News was not immune to, though it fared better than most. From 2008 to 2020, newsroom employment at U.S. papers dropped from 71,000 to 31,000, according to Pew Research Center. Circulation and advertising revenue have also declined as readers increasingly turn to the internet for their news.

At the height of The Buffalo News’ circulation in the ’90s, the paper sold 300,000 copies a day and made a million dollars a week, former investigative reporter Jim Heaney said. The paper’s average daily circulation last year was 56,000, according to the Alliance for Audited Media.

Heaney left the paper in 2011 after 25 years to take a buyout and start a nonprofit investigative news outlet. He could see “the handwriting on the wall” as executives made cuts to the paper without trying to improve the product.

“The strategy not only at The Buffalo News, but I think throughout the industry, is don’t reinvest in the product to make it better. Just cut. Just cut,” Heaney said. “Raise your prices, give readers less, and charge them more.”

Since leaving, Heaney has tracked the cuts in the newsroom, noting that Lee “made a bad situation worse.”

As part of its efforts to centralize operations, Lee made changes to News employees’ benefits, including their medical insurance, dental insurance and 401k administrator, at the end of 2022. The company held a nine-day open enrollment period that several employees called “rushed,” and in 2023, when the new plan kicked in, many could not access their benefits.

Insurance cards were delayed, and several people were told that their usual health care providers were suddenly out of network. Some had to pay out of pocket, though they were told they would later be reimbursed. Lee also made changes to the payroll management system, resulting in mistakes with paychecks, deductions and flex credits. Four months later, in April, people were still having issues, many of which involved prescriptions.

“They’re literally saying, ‘Yeah, once this stuff’s recoded, everybody will get a refund,’” said John Fletch, a production employee and the president of Buffalo Local Mailer Union #81. “I’m like, ‘You’re borrowing money from the employees. Do you realize how ridiculous that is?’ We’ve got mothers in there, single mothers that had to choose between medications and food. That’s how bad it’s gotten for a few of them.”

‘A human toll’

Amid all the cuts and changes, morale among the News’ journalists has plummeted. The newsroom is quieter these days. Fewer people come into the office, which has become a “difficult place to be,” Harris said. In April, the union’s executive committee notified Lee that it had unanimously issued a vote of no confidence in the company’s executive team.

The cuts have compounded the stress reporters have faced doing their jobs, said Stephen Watson, who covers development, government, crime and schools and is the union’s vice president of contract administration. During his 22 years at the News, he can’t remember a period when there have been so many “devastating” stories in such a short stretch of time.

Watson helped cover many of them, including the May 14 shooting at a Tops Friendly Markets supermarket. Part of Watson’s job involved digging through the shooter’s racist writings, which he said were difficult to read.

“I’m white. My wife is Black. I have a 9-year-old son. This really hit me hard, just as it hit the community hard,” Watson said. “You take things to heart sometimes. As a reporter, you try to have remove, but it’s hard not to.”

Stephen Watson first worked for The Buffalo News as an intern in college. He returned to the paper full time in 2001. Watson wants to finish his career at the News but knows that’s unlikely. “It’s painful to see some of what’s happened in the last three years.” (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

When deadly winter storms hit on Dec. 23, Watson lost power while tracking outages for the paper. Watson notified his editors, who asked him to reach out to his neighbors and write a story about enduring a blizzard without power. Afterward, he continued working even though he was supposed to be on vacation that week and later helped cover a house fire that killed five children, the grandfather of whom works at The Buffalo News.

On Jan. 2, Watson was watching the Buffalo Bills-Cincinnati Bengals game when he got a text from his editor. Bills safety Damar Hamlin had just collapsed on the field, and the paper wanted a story about Bills fans’ reactions.

“I tend to have a stiff upper lip when it comes to these things, but I can see it in the faces of some of my colleagues. It’s taken a toll. It’s taken a human toll,” Watson said. “I don’t think they (Lee Enterprises) understand the value we provide, the service we provide to the community, the work that we’re doing here under difficult circumstances.”

Though reporters are quick to point out the important work the paper has done, they acknowledge that some coverage areas have taken a hit as the newsroom has shrunk.

Political coverage is one such area, said McCarthy. Without an Albany bureau chief, the last legislative session was covered from 290 miles away. A local congressional race that would have had three reporters covering it instead had one — McCarthy. He was also the primary reporter for the gubernatorial election.

“There was one congressional election we barely covered.” McCarthy said. “I was appalled by it. I couldn’t do everything.”

As part of the budget cuts, the News has paused hiring. One of the openings affected is a new equity and culture reporter position, which had been a priority for executive editor Rayam, especially given the May 14 shooting, Harris said. Now, the position will go unfilled. In all, the newsroom has lost 13 jobs over the past year.

Rayam has been working to reorganize the newsroom to accommodate the cuts and has told journalists that they will need to be ready to prioritize some coverage areas while letting others go, Sommer said. Accepting that has been difficult.

“We’re used to trying to cover all the things that seem to be particularly important and shouldn’t go unnoticed as much as possible. It’s really hard to let go of that,” Sommer said. “It’s a kind of civic responsibility we each feel in the areas that we write about.”

‘Taking all of the Buffalo out of The Buffalo News’

With little information forthcoming from Lee executives, many employees at The Buffalo News are uncertain about their future.

Right now, 160 positions are in jeopardy due to the News’ announcement that it would outsource printing to Cleveland. Publisher Tom Wiley has acknowledged that the move will likely affect deadlines, The Buffalo News reported. Stories about nighttime Buffalo Sabres or Bills games might not make it into the next day’s paper, Harris said. He also worries about incomplete election night coverage.

The three-hour drive from Cleveland to Buffalo runs along Lake Erie, which could pose problems when there is heavy snow, accounting clerk Alva Hill said. Readers and businesses may face delays in getting the paper.

Accounting clerk Alva Hill has been at the News for two and a half years, and during that time, her job duties have changed “dramatically” because of Lee’s outsourcing of Buffalo-based jobs. “Their goal is to centralize everything,” she said. (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

“They’re taking all of the Buffalo out of The Buffalo News,” said Hill, who also serves as the Buffalo Newspaper Guild’s treasurer. “The newspaper press is a part of this community, and when you take that away, you’re taking away from this community.”

In February, the News reported that the deal to sell the paper’s old office building fell through. Uniland Development Co. had agreed to buy the property for $9 million in September but backed out one day before the contract expired because of low market demand for downtown office space.

That has led to some concern that Lee will impose further cuts, Harris said, though he noted that if Lee closes down the News’ production facility, then it can package the two properties together. Development downtown slowed last year, but 2023 is “more promising,” local digital outlet Buffalo Rising reported. Hundreds of residential units are being added, and a couple hotels are undergoing renovations.

Sommer said one question the union has been asking is how it can prevent further cuts, especially as its numbers dwindle. He wonders if a wealthy, civic-minded person might want to acquire the paper, but acknowledges that is a long shot.

Enterprise reporter Mark Sommer has been at The Buffalo News for 23 years. During that time, he’s watched the newsroom shrink and his coverage responsibilities grow. He worries those cuts will accelerate under Lee. “We don’t want to wind up like newspapers that have three- or four-day-a-week delivery that are just a pale reflection of their former selves.” (Photo: Moaz Elazzazi)

Union leaders at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said that they don’t see a future where the cuts stop. To work in the journalism industry is to always be bracing for the next layoff, said United Media Guild vice president David Carson, especially when corporate owners control local papers. But both he and Gordon said that Lee is not the worst newspaper owner out there.

Unlike Alden, Lee is not an investment firm and does care about staying in the newspaper business, Gordon said. And unlike Gannett, the largest newspaper chain in the country, Lee worked out a deal with Berkshire Hathaway that will likely allow it to avoid having to refinance its debt every few years.

“I’d say that the two things to be optimistic about would be the manageable debt and the fact they’re committed to newspapers,” Gordon said. “The bad news is, do they have a plan that works?”

But for the employees at The Buffalo News, Lee’s recent actions have given the impression that it is following in Alden’s footsteps. Though the paper had issues prior to Lee’s arrival, workers were mindful that their circumstances were better than those at other papers.

That may no longer be the case.

“Somehow we’ve avoided the worst of what the industry has had for years and years,” Sommer said. “Now, the question is, are we going to be able to continue to avoid it? If not, how much time do we have before it really gets bad?”

This story was updated to identify Alden’s description as an investment firm.

Want to learn more about this story? Poynter is hosting a live Q&A discussion on Twitter Spaces with media business reporter Angela Fu and managing editor Ren LaForme on Wednesday, April 26, at 4 p.m. Eastern.

Have a question you’d like us to ask? Send an email to social@poynter.org and we may include it in our discussion.

To the TNG, if they’re reading this: Think back. Back to 2017 when you let them outsource my dept. for the promise of $7M in new revenue, which they never received. Did you see the writing on the wall then? I did. Did you mourn the loss of our dept? We did. Did you think you would be exempt forever from these changes?

News retiree here. This tragic article misses a couple of interesting points. One, stated in a staff meeting before I retired, was from our then-editor, Mike Connolly, who was asked about the newsroom budget under Buffett. He said there wasn’t one. He was allowed to spend whatever he thought was necessary. He said working for Buffett was only time in his career he never had to prepare an annual budget. The second point is that Lee’s acquisition of the News also included Buffett’s other papers, and that it left Lee owing Buffett $576 million at 9% annual interest. Here’s the story we ran: https://buffalonews.com/business/local/buffalo-news-sold-to-lee-enterprises/article_d45d74f7-d85c-5516-8fe9-d07c22ef9314.html It was obvious from Day 1 that News advertising circulation, already tanking, was not going to support that debt load. Then the pandemic hit within a month after the deal was announced. A large cadre of news staffers left after the new Guild contract of late 2021 froze pensions. For a staff that largely comprised old-timers, there was no reason to stay any longer. And with 7-day home delivery now costing about $1,000 a year and the paper down to 24 pages most days — including the seemingly daily full-page house ads showing Sheila Rayam leaning against a wall — it’s just a death spiral that accelerates every week.