By now, most of us are used to living in “unprecedented times.” But just how unprecedented is Joe Biden’s decision to drop out of the 2024 presidential race a little more than three months before Election Day?

Occasionally, incumbent presidents have decided to not seek reelection. But dropping out midcampaign is incredibly rare. And it has never happened this close to an election.

Biden’s decision is a “huge earthquake,” said David Greenberg, a presidential historian at Rutgers University.

John J. Pitney Jr., a professor of American politics at Claremont McKenna College, said, “There is no good analogy.”

The two closest political shake-ups to Biden’s were withdrawals by President Harry S. Truman before the 1952 election and President Lyndon B. Johnson before the 1968 election.

Both Truman and Johnson had assumed office following a president’s death and served a full term of their own; they each would have been eligible to run for a second full term had they wanted to. But following poor showings in each of their respective New Hampshire primaries in 1952 and 1968, both exited the race.

Truman withdrew his name from the presidential election on March 29, 1952, or 220 days before Election Day. Truman, who was suffering from low popularity amid the Korean War, dropped out less than three weeks after losing the New Hampshire primary. (In that era, there were relatively few primaries; in many states, party insiders controlled the nomination process.)

Ultimately, Adlai Stevenson II won the Democratic nomination but lost in the general election to Dwight Eisenhower, a five-star U.S. Army general from World War II who ran as a Republican.

Johnson dropped out of the race March 31, 1968, 219 days before the election. Johnson — who had become broadly unpopular because of another war, Vietnam — had not formally filed to run, and was on the New Hampshire ballot only as a write-in. But after a poor showing, and facing primary challenges from two strong contenders, Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy, Johnson dropped out.

In the end, Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was nominated but lost the general election to Richard Nixon.

Biden’s move is far closer to Election Day — 107 days — and comes after all Democratic voters have had their say in the presidential primaries.

A few other examples are even less similar to Biden’s.

President Calvin Coolidge forswore another term, but he did so with 15 months to go, in summer 1927, Greenberg said.

In 1976, Republicans headed into their convention in Kansas City, Missouri, without knowing whether their nominee would be the incumbent president, Gerald Ford, or the conservative insurgent Ronald Reagan. Ford won the nomination but lost the general election to Democrat Jimmy Carter; four years later, Reagan won the nomination and the presidency.

How will delegates decide?

Now, the formal decision over Biden’s successor as nominee is left to the delegates attending the Democratic National Convention, running Aug. 19 to Aug. 22 in Chicago.

When voters cast ballots during the Democratic primary season, they were technically choosing delegates for a candidate. The delegates allocated will formally decide the successor as nominee during the Democratic convention.

There are about 4,000 regular Democratic delegates earned from primary results and more than 700 “superdelegates” consisting of party officers and elected officials.

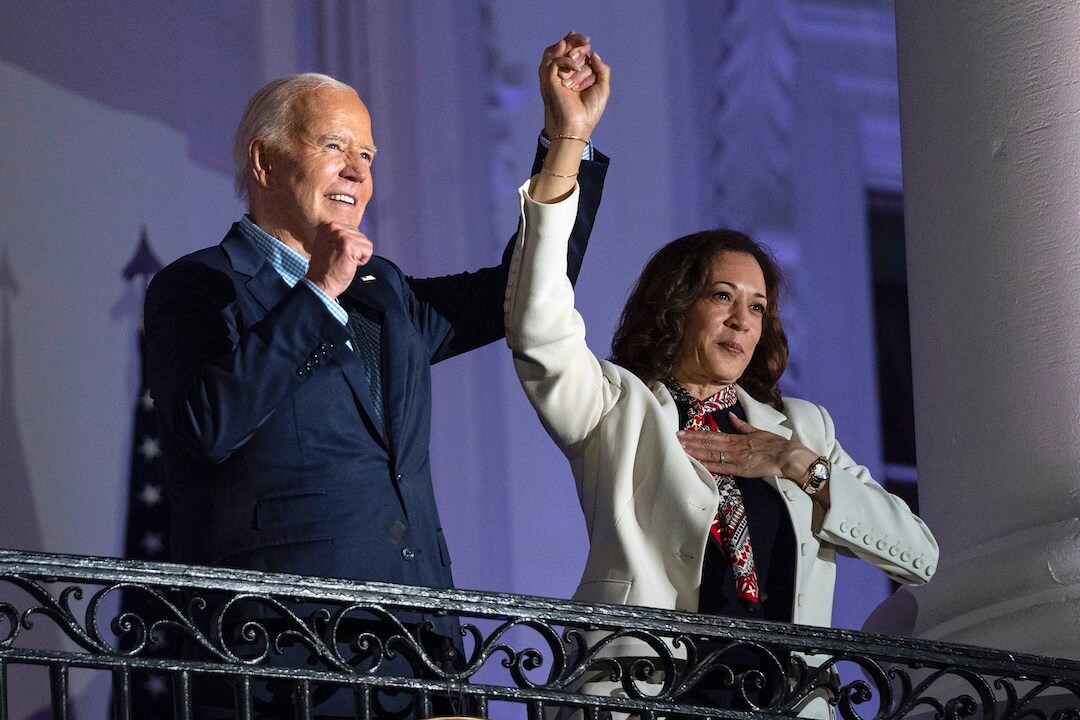

The rules allow for delegates to vote their consciences, but because these delegates are almost entirely pledged to Biden, his endorsement of Harris should carry significant weight, experts said.

Biden’s quick Harris endorsement may even be enough to keep alternative contenders from seeking the nomination.

There will need to be a separate contest to select the vice presidential nominee. The same delegate voting system holds for the vice presidential nomination as it does for the presidential nomination.

This fact check was originally published by PolitiFact, which is part of the Poynter Institute. See the sources for this fact check here.

Comments