MILWAUKEE — As I sit here at the Republican National Convention and think about conventions past and present, it would be an obvious thing to dwell on how they each shaped American politics.

Instead, as a journalist covering my 14th party convention — No. 15 will be next month at the Democratic confab in Chicago — I’ve been thinking a lot about the role of technology in shaping how these events are covered.

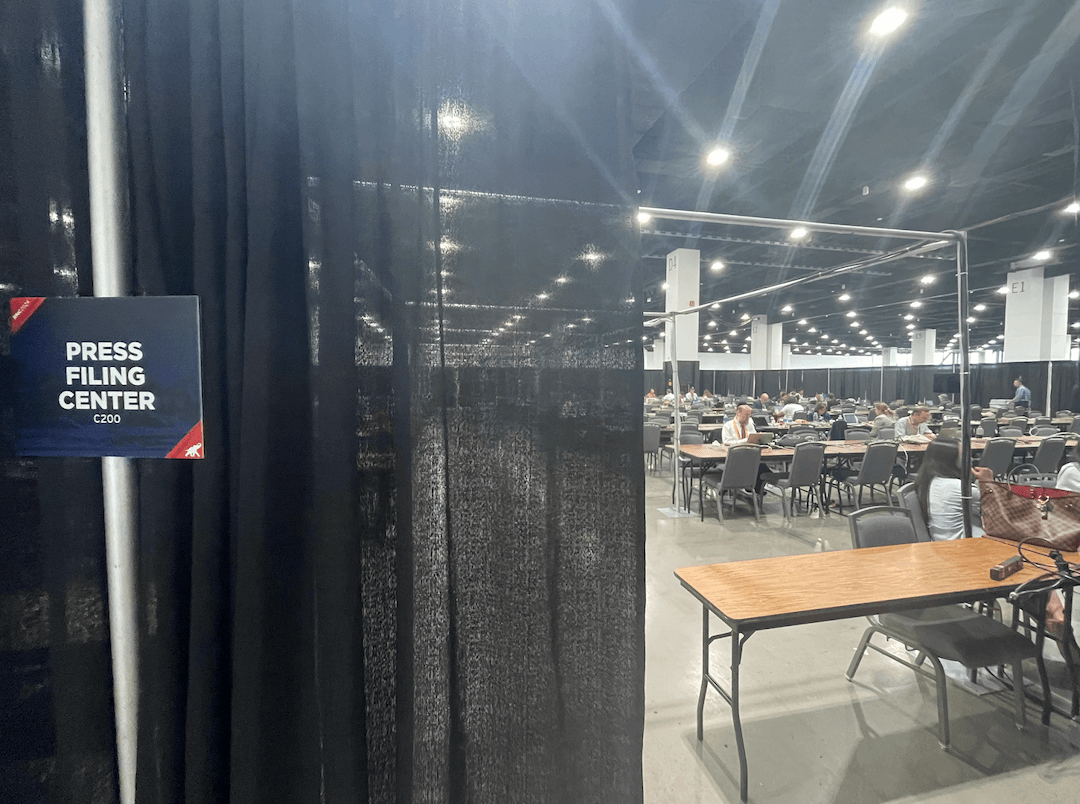

Visually, there’s almost no difference between how the convention hall and floor looked when I covered my first one in 1988, the Democratic convention in Atlanta. Say what you will about political graphic design, but no convention in decades has dared break from the traditional look: a fancy backdrop for the podium in some mix of red, white and blue, culminating in a balloon-and-confetti drop when the presidential nominee finishes their acceptance speech. Even the cavernous press filing centers have the same blue curtains and the same quiet hum of activity.

Physically, conventions are also set up exactly the same way. If you want to interview a delegate or a member of Congress, you secure your floor pass, you stretch and squirm your way through the throngs in the aisles, and you make your way to the appropriate state, navigating by vertical signs that haven’t changed visually in decades. Then you go up to someone wearing a garish outfit that’s laden with partisan accoutrements and say, “Hi, can I ask you some questions for my story?”

Under the surface, though, the experience of being a reporter at a convention is very different today than it was when I started in this line of work.

In a good way.

Technology may not have been an unalloyed good in other areas, but for covering political conventions, it has been our friend.

At that first Democratic convention in 1988 — about a year after I was packed off to summer journalism school with a portable manual typewriter — I was working for a small photographic news service called Consolidated News Pictures, run by the late Arnie Sachs and his sons Howard and Ron. Back then, the film was black and white and had to be developed by hand in a mobile darkroom that my colleagues carted into the arena. My colleagues allowed me to take pictures to be shared with clients, but my primary task was to literally bring rolls of film back to the workspace to be developed. In, out, in, out, having to get through security checks each time. We communicated with each other by walkie-talkie.

Easily shareable color images were still in their infancy, as was the notion of digital photography. When I worked with Consolidated to cover the 1989 inauguration of President George H.W. Bush, I was floored when my colleagues told me that some of my images — ones that I had tripped the shutter remotely using something like a TV remote control — had been scanned into pixels and sent by phone lines to a client in Japan, for immediate publication.

In time, digital photography would prevail, and now I don’t even use a camera anymore; I just use my cellphone. I can now take a photograph of a political celebrity and immediately send it out on social media, with a speed that would have blown my 1988 mind. The same device allows me to send a variety of photographic options to my editors that they can run with my articles.

I still worked for Consolidated for the 1992 Democratic convention in New York, but then I was hired as a reporter by National Journal magazine, and there I had the good fortune of working for a company that produced a daily newspaper for the transitory convention “community.” The large staff of National Journal Convention Daily went to both conventions and filed every morsel of news that we could. (The ad revenue was amazing; it practically carried the rest of our publication for the next three years of the cycle.)

To do it, National Journal had to ship heavy desktop computers and monitors to the media sites in 1996 (San Diego for the Republicans and Chicago for the Democrats). The evolution of laptops made this logistical trick a bit easier by the time of the 2000 conventions (though sadly, I was only sent to the Republican one in Philadelphia that cycle). It was not unusual for us Convention Daily reporters to have to call in a story on a pay phone or fax it in. These are concepts young’uns will never have to experience (and good for them).

In time, cellphones would take over from walkie-talkies and pay phones, but even first-generation cellphones — useful mostly for calls, not web searching, photography or video — were still primitive compared to today’s models.

I remember using an earpiece (wired) for my phone for the first time in 2004 for the Democratic convention in Boston. By 2008 at the Republican convention in Minneapolis, I recall being able to sit in the press stands inside the arena and post articles for my now-defunct publication, CongressNow, using the marvel of Wi-Fi. Now, that’s de rigeur. (Kudos to Milwaukee convention planners this year: The Wi-Fi inside the Fiserv Forum and the associated buildings is excellent.)

Today, we can easily take and upload video (a task that once required an analog camcorder) and then share it with the world instantly, thanks to social media. When supporters of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders stormed the Florida Democratic delegate breakfast in Philadelphia in 2016 to protest Florida Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz’s handling of their candidate’s demands, I was able to take photographs in quick succession and upload them in real time to Twitter and share them with my editors at the Tampa Bay Times.

The process continues: At this year’s Republican convention, I’ve added artificial intelligence to my portfolio for the first time, at least in a limited, tightly controlled way. I’m now able to point my iPhone to a speaker or a group and have a rough-and-dirty transcription of 30 minutes of audio within minutes. This eases the process of finding claims that PolitiFact can check, or quotes to use in a story.

The glorious march of convention-related technology hasn’t been restricted to personal communications devices, either. I first used Airbnb at the 2008 Republican convention and have done so at both 2016 conventions. By 2016, Uber had become a vast upgrade over fruitlessly trying to hail a taxicab after a late-night convention session ended (or after a boozy after-hours party).

So, a lot has changed. But thankfully, despite news cutbacks over the years, every convention presents an opportunity to reconnect with old journalist colleagues I haven’t seen since the last one four years ago, especially given the increasing trend of remote work.

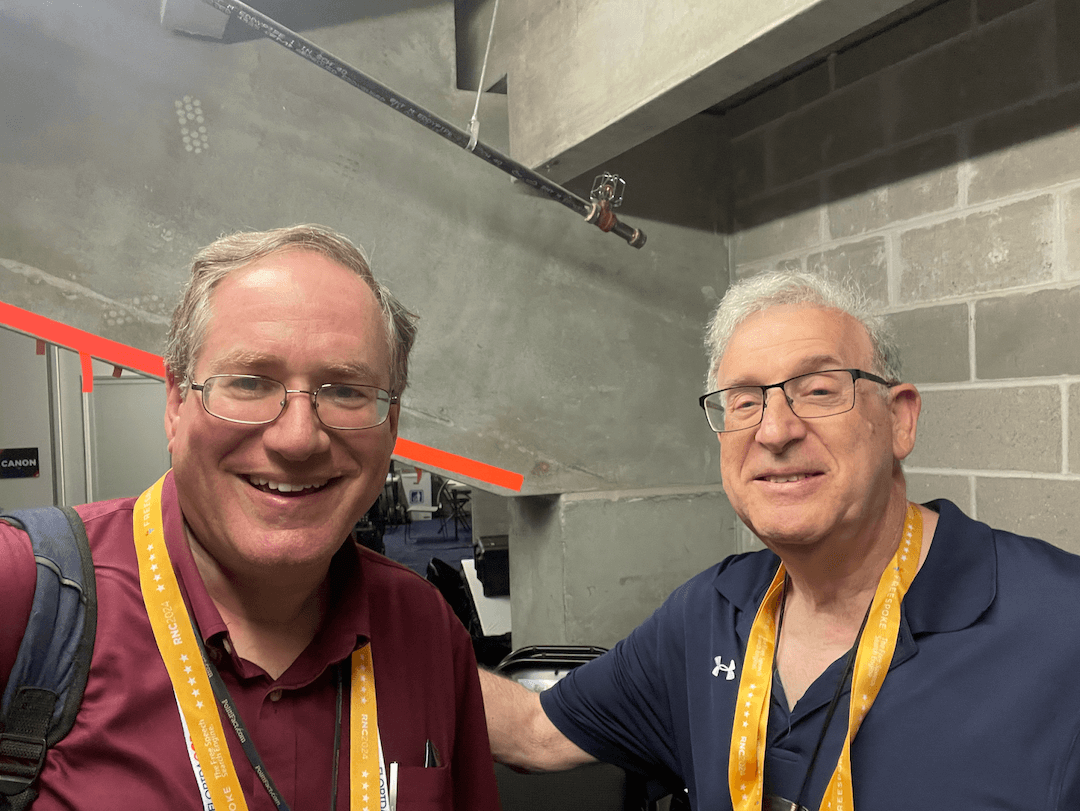

Remember Ron Sachs, who I first worked with at that convention in 1988? I bumped into him on the plane out to Milwaukee. I said, “I know where you’re going.” He said, “I know where you’re going.” And when I was casing the facilities the night before the convention, I made a point to find him in the newfangled digital darkroom behind the podium.

The author with Ron Sachs at the Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee, July 14, 2024. (Louis Jacobson/Poynter)

Louis Jacobson, PolitiFact’s chief correspondent, is covering the Democratic and Republican conventions this year for PolitiFact and two of its partners, the Tampa Bay Times and the Dallas Morning News.

Comments