The moment when a bullet pierced the ear of former president Donald Trump was a traditionally slow period for news consumption. That day of the week and time of day — Saturday afternoon and early evening — is a universally low-volume slot for news websites, radio and cable television.

As news of the shooting broke, I took note of the friends and family around me, who occupy the entire continuum from news junkie to news avoider to completely disengaged. How were they feeding their own need to know what happened?

The Trump rally in Pennsylvania was being televised live by Fox News and a few other outlets. It was witnessed by thousands of people and dozens of reporters and photographers. Yet it still took a solid hour to confirm that those had been gunshots, that Trump had been nicked by a bullet and that the gunman was dead.

I launched a short survey and asked my friends, family and social networks to describe what news they consumed and how satisfied they were.

This was not at all scientific. Journalists and Gen Xers were overrepresented, as were liberals. Despite the lack of rigor, the results revealed some clear divides. A small portion of the 126 respondents were nimble news junkies, bouncing between brands, platforms and devices. They could describe the relative strengths and weaknesses of different newsrooms and even individual journalists. They kept at it for hours and even though the news was unpleasant, they found the coverage engaging.

But a much larger portion of the people who filled out the survey described a clear set of strategies that would limit their exposure to ongoing reporting. They talked of protecting their time and their emotional well-being, of needing to be informed and wanting to avoid feeling manipulated or disrespected.

I reached out to Benjamin Toff, one of the authors of “Avoiding The News,” a book that delves into the growing habits of people who deliberately choose to limit their exposure to news.

He noted that both political news and breaking news are generated in a way that creates a huge gap between what many people want and what they are served.

“You can understand the sort of incentives of the news organizations to cater the coverage to (news junkies),” he said. “I do think it is undermining the relationship with the rest of the public.”

Political reporting is the beat most akin to breaking news, particularly in a presidential election year. Political reporters are deeply sourced and deeply competitive. Their work is designed to serve the small portion of people who come back again and again, who thrive on knowing the latest developments and the smallest increments of information. Those people drive much of the traffic to political news stories. They are the loudest signal.

The rest of the audience has to hunt and peck through the vast quantity of information, analysis and opinion to find what they need. Think of it like a restaurant. The news is a massive, all-you-can-eat buffet. Sure, you can find something healthy and take just a small portion. But it’s up to consumers to figure out what door to go in, how to get to the stations with the food they like, and how much they want on their plate.

Who doesn’t love a buffet? Lots of us.

How we first heard of the shooting

The majority of people who responded to my survey, 37%, heard about the shooting from friends and family. Most of them got a direct text message or other direct contact. Some of them heard about it in a group chat.

Push news alerts were the second most popular vehicle for discovery at 31%. Several of the folks who heard from a friend said that person got a push alert. In the ecosystem of news consumers, junkies and those who like to be in the know are driving their friends and family toward the news when something dramatic develops.

Social media discovery came in a distant third, and Instagram was the winner among the platforms, which probably indicates which social media platform people scroll on Saturday afternoons.

Eleven people in my group learned of the shooting because they randomly went online, and six people turned on the TV to watch the evening news. Two people were watching Fox News live. Two people were driving in a car and listening to the radio.

What happened next

I really wanted to know what people did next. Where did they go to find out if it was true? Did they get what they needed?

Here’s how it broke down:

- One-third of the respondents went to a browser and mostly opened up a well-known news site, although some of them went to search.

- A quarter of them went straight to a news app.

- Fifteen percent went to a social media site. Several of the folks who opened up X pointed out that it used to be much better during breaking news.

- Just over 10% turned on the TV.

- Seven people did absolutely nothing to gather more information.

- One person phoned a friend.

Separate camps

I asked people how much time they spent looking for information and how they felt. Here I could see the respondents divided into distinct categories. The news avoiders got out fast.

At what point did you feel you had enough information, my survey asked.

Less than five minutes in.

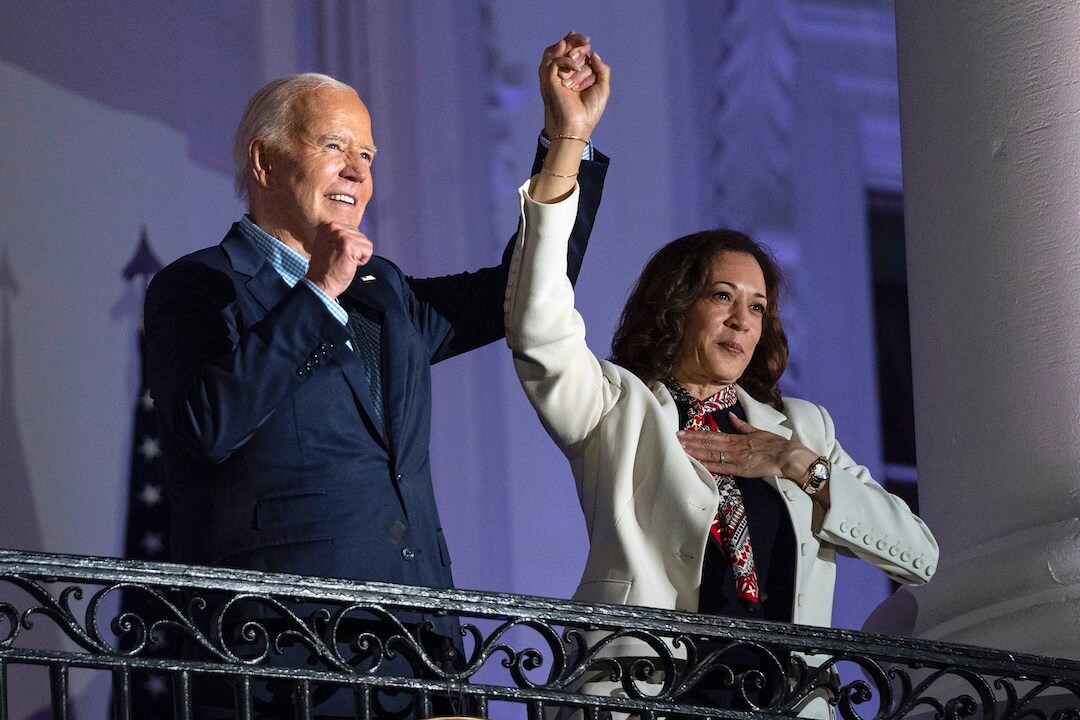

Almost immediately, when I saw the raised fist photos I felt like it was a publicity stunt.

Almost instantly. It is overwhelming being constantly fed negative news/information.

I wish I could just get the news without all of the hype. I have to spend a lot of time sorting through sources to just get to factual information. I don’t want to spend so much time on politics.

These reactions tracked closely with Toff’s research. For his book, he interviewed hundreds of people and discovered that a growing group of people find consuming news unpleasant and are developing strategies to cope.

“Some news avoiders have decided to deliberately change their habits,” Toff said. “Some will talk about it being very frustrating to try to make sense of news if they’re consuming directly, because they have the sense that they have to be skeptical of whatever the agendas are of the news organizations and journalists.”

Toff learned through his research that both news avoiders, as well as people who are politically disengaged, are much more likely to rely on personal contacts.

“They would actually rather have trusted friends or family, kind of playing the role of helping them navigate what’s trustworthy and what’s not,” he said. “And so (your survey respondents) sound like a familiar response.”

There was a mid-level group of people who fall between the avoiders and the high-volume consumers who I am now naming the news simplifiers. These folks had clear stopping points in their quest for information. They went beyond the headlines and they knew exactly what information they needed to understand the events. In response to the question about when they had enough information, they said things like:

When I knew the shooter was dead.

Once I knew the shooter was down and Trump had walked off scene on his own, it seemed unnecessary to continue to watch for more details that would only be speculative and partisan.

When the news media started repeating themselves.

The news junkies demonstrated clear awareness in their answers to the same question that they are a small subset of the population. They said things like:

I’ll never be satisfied.

I felt a strong need to understand what was happening, gain all perspectives of the event, and become maximally informed. This was a national moment.

I opened all my news apps: CNN, PBS, New York Times, BBC, NPR, Fox, etc. and visited the websites and monitored their “live updates” sections.

Finding a better way

In Toff’s book, he and his co-authors document that news avoiders are more prevalent among younger people, women, the sociologically disadvantaged and politically disengaged. This is a problem.

American journalism has long evolved to serve wider and wider audiences. The growing number of people who feel alienated from the news is a growing threat to democracy. “Although many (news avoiders interviewed for the book) were confident, at least in theory, that they could use digital tools to find information they needed,” Toff and company wrote, “… they lacked the habits and heuristics used by news lovers to make sense of that information, they often felt uncertain about what to believe.”

I saw that in real time. I watched several people at first reject the idea that Trump had been shot. They thought it was a staged event. Then, they struggled to sort through the details.

“Is this real? Did civilians notice beforehand?” my youngest daughter texted me with an Instagram link to the video of the shooter on the roof with rally attendees trying to get law enforcement’s attention.

Among the many recommendations the authors make for journalists and newsrooms: Package and deliver content specifically for news avoiders. Don’t make them go to the giant buffet.

What would that look like?It would be short and clear; “simple brevity” is the phrase Toff uses.

There would be easy-to-navigate features that would provide background information for people not up to speed on an issue. This might be activated by hovering or turning on a button on the page or app.

The entire experience will be customizable. And it will also be delivered on many other platforms.

I asked people to tell me their favorite way to get news. Their answers were all over the place. In addition to the more predictable and familiar responses, like news apps and specific brands, I heard:

Passively

Filtered by comedy

Friends reading breaking news off their phone

It used to be Twitter! Now, not so sure

I prefer to get news a day late

TikTok

YouTube

We have to give them what they want. That means paying attention to the increasingly unpleasant experience that people are having when they are consuming the news and offering them an alternative.

Comments